News

A SCINTALLATING, RACY READ

Ken Piesse reviews ‘The Cricketers of 1945, rising from the Ashes of World War Two’ by Christopher Sandford, available from cricketbooks.com.au

Don’t you love the feeling of being so enveloped in a new book that you can be found in the same easy chair hours later, totally riveted?

‘The Cricketers of 1945’ is absorbing, lyrical and impossible-to-put down. For me, it entertains like no other cricket book this calendar year.

Christopher Sandford is an evocative storyteller whose formidable backlist includes biographies from John F Kennedy and Roman Polanski through to Paul McCartney and the Stones.

Christopher Sandford is an evocative storyteller whose formidable backlist includes biographies from John F Kennedy and Roman Polanski through to Paul McCartney and the Stones.

Cricket lovers are fortunate that Sandford so adores cricket. His masterly ‘Final Innings’ (2020) was the joint winner of the Cricket Society and MCC Book of the Year.

From biographies of post-war giants Imran Khan, Tom Graveney and Jim Laker and Tony Lock (in a combined volume), Sandford’s character embellishments are vivid and illuminating. Of all his cricket titles, ‘1945’ is my personal favourite, celebrating so many of the most remarkable who lived and loved, some not knowing their lives were out of control due to the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder.

From Bill Edrich, Bill Bowes and the heavily afflicted Harold Gimblett through to the irreverent Aussies Keith Miller and his equally anti-authoritarian mate Cec Pepper, Sandford brilliantly captures the mood and spirit of the war years. Frontline service changed so many and reinforced that life was there to be lived.

It’s racy in parts, befitting the carefree times after victory was proclaimed.

Edrich, a randy soul with prematurely receding hair and a high chirpy voice, married five times, a ‘record’ matched only by South African contemporary Hugh Tayfield, appropriately known as ‘Toey’. Once Edrich took a fancy to a girl in Baker Street, but not having enough money to find a room, had sex with her against a tree in Regent’s Park. ‘His basic courtship method was direct,’ says Sandford. ‘He hugged and then started undoing buttons.’

For years Edrich’s recurring nightmare would centre around seeing one of fellow airmen at Blenheim waiting to take off on a mission. The man’s face would become a skeleton. ‘So many of my pals didn’t come back,’ Edrich said.

One of Edrich’s earliest wives said her husband was notorious for checking out the talent across a room in mid-dance. He couldn’t help himself.

Edrich and his Middlesex teammate Denis Compton were identified in early 1948, an Ashes year, as England’s most dangerous batsmen.

When asked to bowl bouncers at the pair, Miller refused and threw the ball back to his captain (Don Bradman), telling him to get someone else to do his dirty business. Compton was one of his best mates and he knew what Edrich had endured during the war. He also knew how Bradman was last in and first out.

Miller had a lifelong propensity for insubordination and remained anti-Bradman until his final days. His matinee-idol looks, wartime exploits, engaging ways and habit for remembering names made him a favourite everywhere. Women clung to him ‘like bees to honey’, said Sandford. Having just met American Peg Wagner, who was to become the mother of his four boys, the freshly engaged Miller boated back to the UK and as Sandford says, ‘was gratified by the number of Australian nurses on board the vessel. ‘Enormous honkers,’ Keith was to write to a pal, ‘like being smothered between two great pillows.’

Cricket’s most famous wordsmith Neville Cardus was another devout admirer, calling Miller ‘the supreme champion every boy wanted to be’.

More than 100 first-class cricketers died in the war, the vast majority English. Among them was Hedley Verity, 38, who had spun England to a famous victory at Lord’s in 1934, Australia’s only loss at cricket’s famed headquarters in the 20th Century

Bill Bowes, most famous for bowling Bradman for a first-ball duck in Melbourne, spent three years of his war in a prison camp. Afterwards, he said his clothes ‘hung off me like a sack’. He’d lost four stone and played only one more Test.

Just over a year after appearing in the middle-order for Watchet in the Somerset leagues, Gimblett was opening the batting for England at Lord’s. He was a tormented genius. At his best he could bat like a supreme ringmaster, with flair and confidence and an arc of 270-degree shots years ahead of his time.

He’d volunteered for the RAF but was posted instead to the fire service where he saw duty in the badly blitzed towns of Plymouth and Bristol. His county colleague Frank Lee, later an umpire, said Gimblett after the war looked a like a scarecrow.

‘He told me about being on duty in Bristol one night an described a row of houses with a little park in front of them. Every time a bomb fell, there was a pink glow and it blew up a piece of someone.’

The Australian AIF team which contested the Victory Tests in 1945 included Miller, Lindsay Hassett and the hard-living 16-stone Cec Pepper from Parkes in country NSW.

Sandford says his liking for a drink and occasional flashes of fiery temper emphasised the aptness of his surname.

‘In 1945 the sight of Pepper walking into a pub was a bit like that of Cary Grant entering a tailor’s shop or Winston Churchill into a cigar outlet.’

His infamous run-in with Bradman in Adelaide when Hassett’s team played a set of matches Australia-wide cost him his representative career. Instead he went to England becoming the highest paid professional player in the world and fathering four sons by four different women, only one in wedlock.

They were different times indeed.

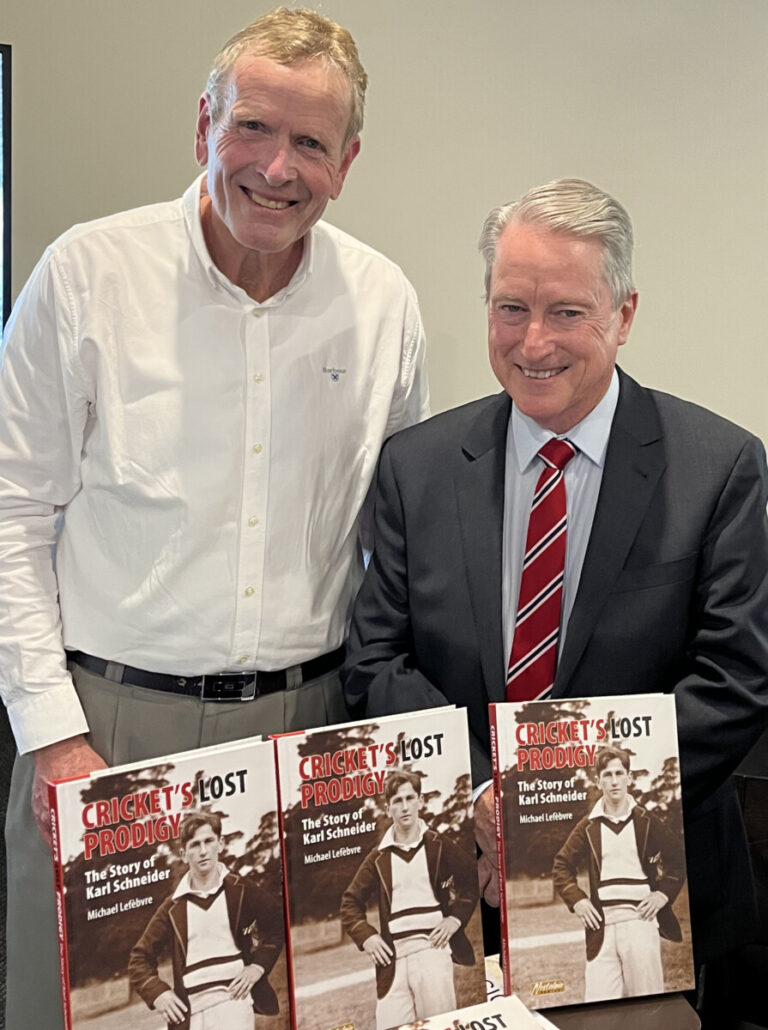

Pictured above: Keith Miller and Cec Pepper during the 1945 Victory Tests.