News

A UNIQUE CRICKET CONTRIBUTION

By Ron Reed

Sportshounds.com.au

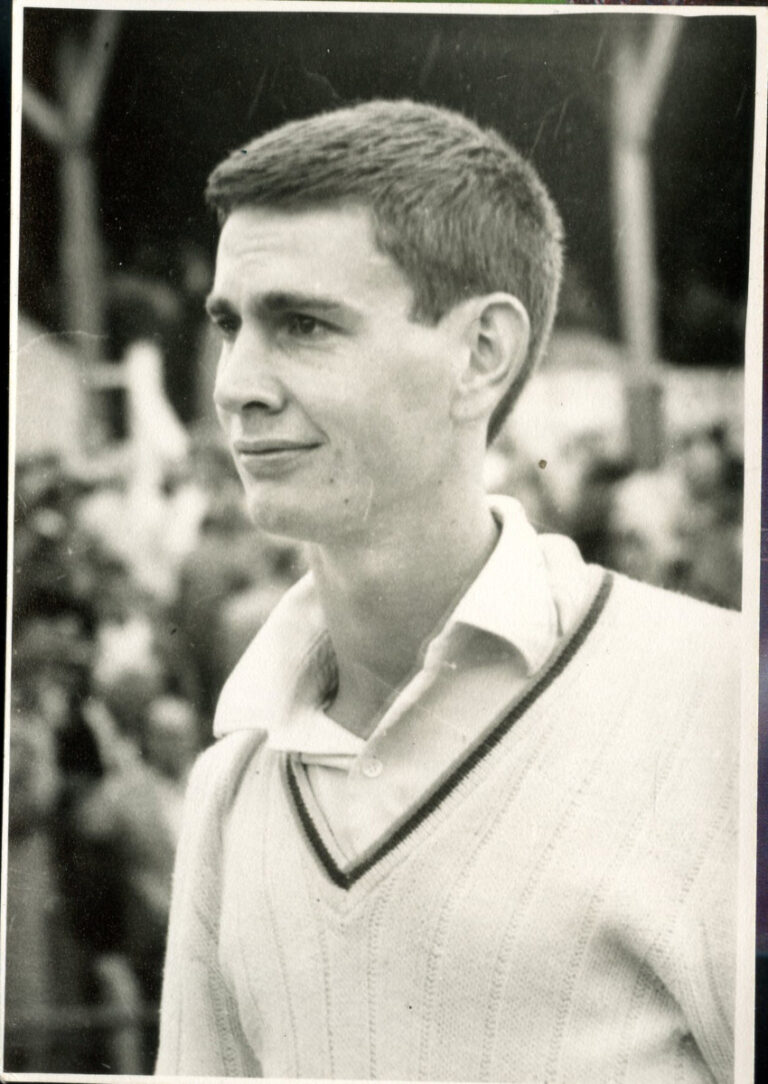

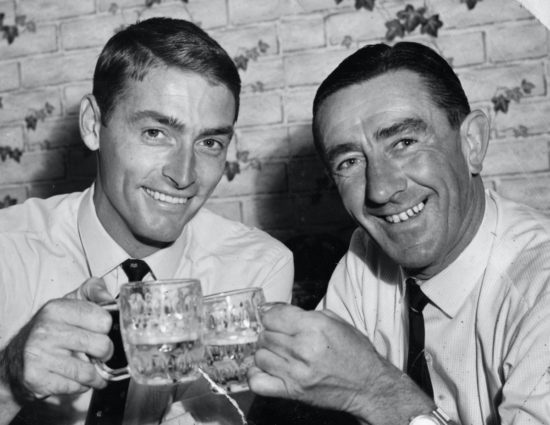

JACK Potter enjoyed two pretty good cricket careers – one as a player and one as a coach, both of which were celebrated in Melbourne on Friday when his biography, Born Lucky, was launched at a lunch put on by the Australian Cricket Society and the Victorian Taverners.

Potter, 82, is a former Victorian captain who averaged 41.22 in 104 first-class matches and got as close to Test cricket as possible without actually ever playing it – he was on the 1964 Ashes tour and was 12th man twice there and once in Australia.

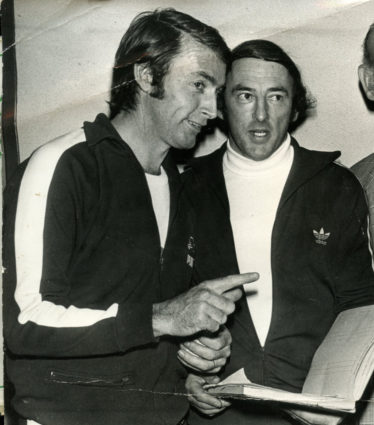

But perhaps his biggest contribution to the national cause was his stint as the inaugural coach of the Australian Cricket Academy when it was established in Adelaide by Cricket Australia and the Australian Institute of Sport in 1987.

But perhaps his biggest contribution to the national cause was his stint as the inaugural coach of the Australian Cricket Academy when it was established in Adelaide by Cricket Australia and the Australian Institute of Sport in 1987.

Potter is rightly proud of his three-year stint there, which saw 30 of 46 boys go on to play first class cricket, and 11 make it all the way to Test and international one-day ranks for either Australia or England, none more successfully than Shane Warne – who he taught to bowl the flipper — and Justin Langer.

But only now has he put it on record just how difficult and frustrating the job was given the scepticism and lack of support the project attracted from the cricket establishment and certain key people in it, notably, he says, the late David Hookes and the then chief executive of the Australian Cricket Board, Graham Halbish.

I don’t recall these issues being big news at the time, or being in the public arena at all, really, but they certainly would be if it was happening now.

Potter says that before taking up the job he had “a prophetic conversation” with prominent Melbourne cricket identity Bill Jacobs who warned him not to trust some of “those clowns” at the ACB.

“In those formative months we met with much resistance, cricket being such a conservative game,” Potter writes. “Many of the first-class players at the time scoffed at the ideas and methods; some on the ABC openly disagreed with the changes we were making.”

A professional physical education teacher while he was playing, Potter was more fixated on fitness than most cricketers of his era and beyond. “It wasn’t uncommon for first-class cricketers in the 1980s to think that a beer and with pie, sauce and chips during a game was a good way to relax,” he says.

He also found that “intense and entrenched interstate rivalry” created a lack of co-operation at a higher level, which contributed to Australia’s declining international performance at the time., which was the reason the academy was put in place.

While the South Australian Cricket Association was supportive, it put forward only three boys in the first year and Hookes, the State captain and its best player, made his disdain clear.

He even went so far as to refer to the AIS as ‘assholes in sandshoes’ and advised some outstanding young players, including future Test player and national coach Darren Lehmann, not to attend, Potter says.

Consequently, it took Lehmann a long time to realise his potential and break into Test cricket.

Consequently, it took Lehmann a long time to realise his potential and break into Test cricket.

Budget issues threatened to send the academy out of business until the Commonwealth Bank stepped in with sponsorship, while Potter also felt that bureaucratic interference was becoming a major problem and that his role and efforts were not appreciated or respected.

Halbish, he says, “had to be consulted every step of the way even though he had little background in playing or coaching cricket. He had great difficulty handing over management and used to call every week with instructions and came to Adelaide once a fortnight to give advice.”

Potter says “my initial conversation with Bill Jacobs was always in the back of mind, now more than ever.”

In a chapter headed “The Last Straw,” Potter says the Academy was invited to send a team to tour the West Indies. He would be the coach. Except that he soon got phone calls from Greg Chappell, Doug Walters and Dean Jones, who all told him Halbish had rung them and asked them to coach the team.

After a testy conversation with the CEO, Potter felt he was becoming the victim of a personal attack. “I hadn’t taken kindly to what I considered to be Halbish’s attempts to interfere in the running of the academy and had told him so.”

The end was nigh.

He and his assistant, Peter Spence, had both become frustrated with the lack of support and the onerous workload, Spence leaving to join the Victorian Institute of Sport.

“In the end I could no longer tolerate the excuses and meddling and after nearly three years of backbreaking work, I was exhausted. I was exhausted,” Potter writes.

“My phone call to Halbish was short and sharp: ‘You can stick your f***ing job up your f***ing arse.’”

“You wouldn’t dare resign.”

“Oh, wouldn’t I?”

“And I did.”

In the end I refused to work with a man I couldn’t trust.”

The Academy continued to churn out superstar players under other coaches, notably Rod Marsh – including Rick Ponting, Adam Gilchrist, the Hussey brothers, Brad Haddin, Mitch Johnson, Brett Lee, Glenn McGrath, Shane Watson and others – and eventually moved to Brisbane in 2004, renamed the Centre of Excellence.

Born Lucky is published in limited edition of 500 by cricketbooks.com.au