Subtotal:

$16.50 (incl. tax)

Description

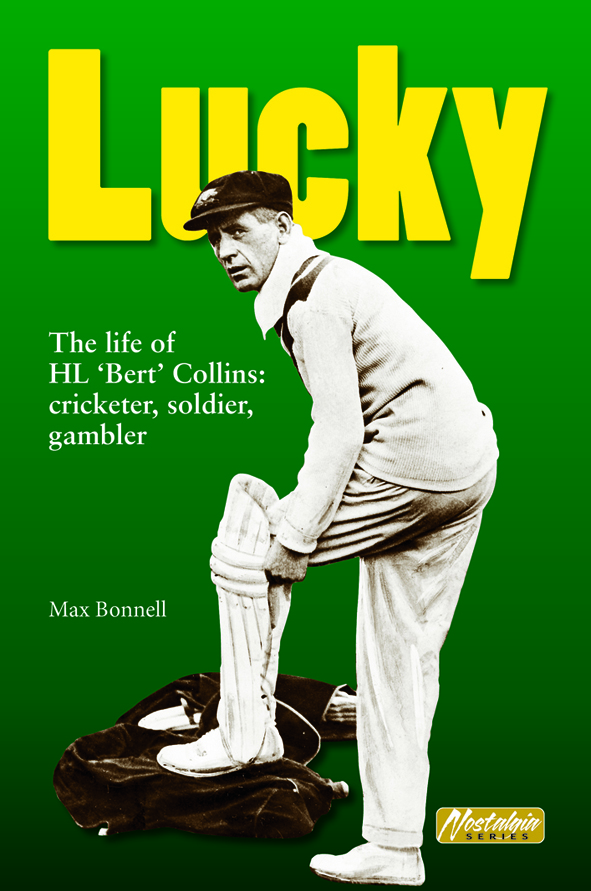

The life of HL ‘Bert’ Collins, cricketer, soldier, gambler. Limited edition of 300, classy hardback, pictorial boards, acclaimed biography, published by Ken Piesse in his Nostalgia series. Also in the series: The Silk Express (Ted McDonald) and The Terror (Charlie Turner)

Additional information

| Published | |

|---|---|

| ISBN | 9780992522827 |

1 review for Bonnell, Max – Lucky, the life of HL Collins

Add a review Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a review.

Related products

-

Gower, David – A right ambition

$16.50 Add to cart -

Sale!

Walker, Max – Cricketer at the Crossroads

$13.75Original price was: $13.75.$6.60Current price is: $6.60. Add to cart -

Sale!

Byrell, John – Thommo Declares! Cricket’s most colourful larrikin

$22.00Original price was: $22.00.$5.50Current price is: $5.50. Add to cart -

Sale!

Robinson, Ray – On Top Down Under, Australia’s cricket captains

$16.50Original price was: $16.50.$4.40Current price is: $4.40. Add to cart

Ken Piesse –

Review by David Frith

Midst the pile of cricket books of ephemeral significance still being published comes a further meaningful offering from Australia. Herby Collins not only led his country through some fascinating Test matches in the 1920s. He was a genuinely interesting character who has been the subject of much speculation. Max Bonnell is among the top rank of cricket researchers, and here he’s done it again: created a detailed story when relatively little background material was readily available. He has tracked down some obscure output from Collins’s own pen in a Brisbane newspaper, and he managed to find some descendants. The title gives a clear indication of the diversity of the po-faced Collins’s activities – and that’s even before looking at his early career as a rugby player.

The author makes it clear that Collins’s own published statements are not always to be trusted. This makes complete understanding of the famous Oval Test of 1926 rather hard to reach. Did he ‘sell’ that contest by persisting with the relatively harmless bowling of Arthur Richardson, or did Hobbs and Sutcliffe win a game of bluff by making the off-spinner look difficult in order to keep him on?

One of the more surprising details is young Collins’s success on the rugby field, in spite of his slight physique. He shared the turf with the immortal Dally Messenger. And when summer came he could go after the bowling when it suited him: he slaughtered Tasmania’s ‘attack’ in a stand of 168 in 55 minutes with Victor Trumper. But his preference was for extreme caution, to grind it out at the crease, often not bothering to wear gloves.

He seems to have exaggerated his service in the Great War, but it was with the AIF team that he began to make a mark. His Test debut came at Sydney in 1920-21, and so many chances off his limp bat went begging that the nickname ‘Lucky’ was bestowed on him. But the inconsistencies come one after the other. Lawyer Bonnell catches him out time and again. It becomes almost funny. Contrary to Collins’s claim, he did not catch Ernest Tyldesley at Trent Bridge in 1921, breaking a thumb in the process. Perhaps he simply had a duff memory. The author sees no alternative but to brand Collins a liar.

There are cricket highlights aplenty, including the mighty Jack Gregory’s record Test century (70 minutes) at the old Wanderers ground, Johannesburg, his stand with Collins thundering along to 209 in 97 minutes. Collins amassed 203 and was carried shoulder-high from the field. Later he bowled 14 overs for two runs as South Africa fought to draw the match. This time he wasn’t toasted by the locals. What a very different game it was nigh on a century ago.

Surprisingly, Collins was once the fastest to a thousand Test runs (18 innings), a record which Herbert Sutcliffe (12 innings) soon took from him, and still holds. Perhaps more importantly, Collins stood up for players’ rights, foreshadowing the Packer revolution of over half-a-century later. His place in cricket history is multi-faceted.

Collins’s dead bat steadied the 1926 Ashes series. His 24 in 2˝ hours secured a draw at Lord’s, and for three hours he batted before reaching the boundary at The Oval, where Australia lost the Ashes. Thereafter it was a case of making a living out of horse-racing, and marrying a 24-year-old when he was 51, a union which didn’t last. His con-man brother was jailed. H.L.Collins even got stuck into the post-war Don Bradman, suggesting that cricket would be better now if he quit.

Once more, the comparison is irresistible: are today’s cricketers anywhere near as interesting as so many of their predecessors?