Description

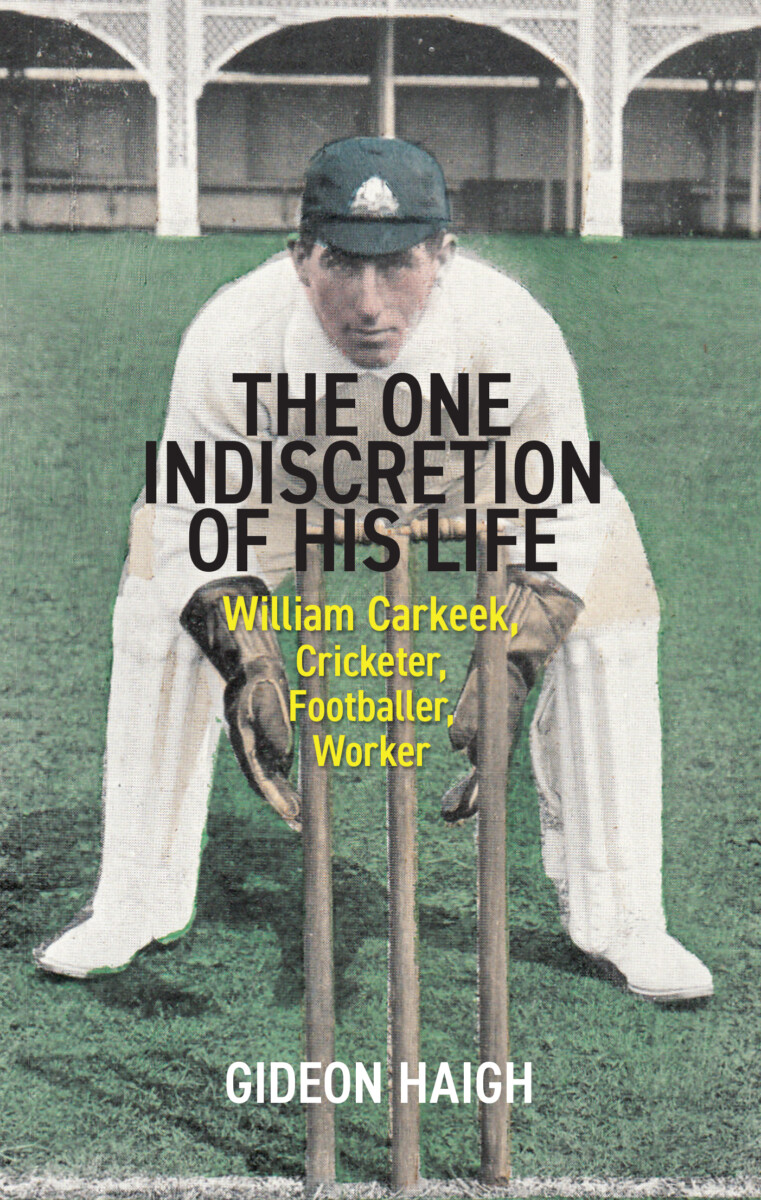

William ‘Barlow’ Carkeek’s story; hardback, with dw. New. 500 copies only printed. This is my last one

Carkeek played for Australia in 1912. His Melbourne district club was Prahran.

Some years ago now, Ian Chappell told GIDEON HAIGH that only three dates mattered in the history of Australian cricket: in reverse order they were 1977, the year of Packer, 1932-33, the summer of Bodyline, and 1912. Quite so, Gideon assented. If the last is obscure, it shouldn’t be: ’The 1912 Overture’ as Ray Robinson called it, where the nation’s leading six cricketers withdrew from a tour of England in protest at the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket’s decision to impose a manager on the squad, marked the eclipse of player power for six and a half decades.

The ‘Big Six’, as they were known, hold to legendary status: Victor Trumper, Clem Hill and Warwick Armstrong are all members of the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame; Albert Cotter, Hanson Carter and Vernon Ransford belong solidly to the ranks of the next best. But what of those who took their place in what, by some lights, was a black leg XI, who returned as one of Australia’s least successful? I first began to consider them decades ago while writing The Big Ship, about Armstrong’s life and times – in particular William ‘Barlow’ Carkeek, a wicketkeeper from Victoria.

When Carkeek was first chosen for Australia, Hill took the extraordinary step of publicly disassociating himself from the selection; when the Big Six imbroglio blew up, Carkeek exhibited no compunction about crossing the picket line, saying as he signed his contract: ‘Might as well be first.’ He clearly owed nothing to Hill and his contemporaries, and in doing so had his supporters. As an anonymous contributor to The Argus, ‘Old Hawburnite’, put it: ‘It is very evident that Mr Hill would let his personal feelings interfere with his judgment when selecting the best men, for he stated in reference to W. Carkeek’s selection that, whatever Carkeek’s merits as a player might be, he would offer the strongest possible objection to his being selected. Now any follower of cricket knows what Mr Hill is driving at. Can any of us afford to throw mud at a fellow cricketer who has been not so fortunate perhaps as we in being able to cover up successfully perhaps the only one indiscretion of his life…’

‘Any follower of cricket knows’? ‘The one discretion of his life’? I remember reading these lines, in those pre-Trove days, on a microfiche reader in the State Library of Victoria in 1999 and being too intrigued for words. What was common knowledge then had in the interim become completely obscure – and not, in fact, directly germane to my task. Still, y’know, note to self: go back one day and have a dig.

It took two-dozen years, but the couple of months after the last Ashes tour proved perfect for the task: Trove, Ancestry, the Public Record Office, National Archives of Australia, the archives of Cricket Australia, the Victorian Cricket Association, Prahran CC, Richmond FC and Essendon FC. It was a sporting story, of course, for not only did Carkeek represent Australia at Test cricket but he won a football premiership and a season’s medal, plus high-class local baseball. But it was also an inquiry into the social conditions of Carkeek’s time, for he was that relative rarity in our cricket a genuinely member of the urban proletariat (variously a grocer’s assistant, a tramways worker, a riveter, a boilermaker and an instrument fitter).

That ‘indiscretion’? This proved an underestimate: it turned out that Carkeek had decidedly rackety personal affairs. The One Indiscretion of His Life encompasses two suicides, two bankruptcies, two colourful divorce suits, cohabitation with a femme fatale to whom he was not married, marriage to another woman who brought to the relationship an illegitimate child, an assault charge and a violent accidental death.

Let others worry about the niceties of the players’ right to appoint their own manager; when he agreed to tour England, which was the only way a cricketer in those times could make a decent income, Carkeek needed the money. With cricket as his passport, Carkeek was able to visit the United Kingdom, the United States, Europe, Canada, Bermuda, Ceylon and Fiji. With cricket as his welfare provider, he enjoyed a better retirement than others worn out by working class toil.

Not that it was plain sailing. That 1912 tour was notable for other reasons: reports of division and drunken misbehaviour forwarded to the Board by that controversially appointed manager, Brisbane’s George Crouch, fingering Carkeek and the team’s other working-class Melburnians, Dave Smith and Jimmy Matthews. That their hand-picked players had apparently played up in the presence of English hosts was potentially a huge embarrassment to the inchoate board and a whitewash ensued. But the Board afterwards arrogated to itself the right to intervene in matters of selection where a player was not felt…well, quite the right sort of chap. The existence of the power was not revealed for another forty years, by the Sid Barnes affair; its vestigial influence was confirmed only three years ago, by the board’s limp performance in the Tim Paine affair. For Carkeek, then, a degree of historical significance can be claimed that is out of all proportion to his on-field achievements – proof again, were it needed, that the past must be accessed by more than statistics.

Additional information

| Year Of Publication |

|---|

You must be logged in to post a review.

Related products

-

Bird, Dickie – My Autobiography, signed by Dickie

$11.00 Add to cart -

Taylor, Mark – Taylor Made, signed by Mark

$16.50 Add to cart -

Knight, James – Lee to the Power of 2

$16.50 Add to cart -

Sale!

Maxwell, Jim – Stumps: the way I see it

$11.00Original price was: $11.00.$8.25Current price is: $8.25. Add to cart

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.