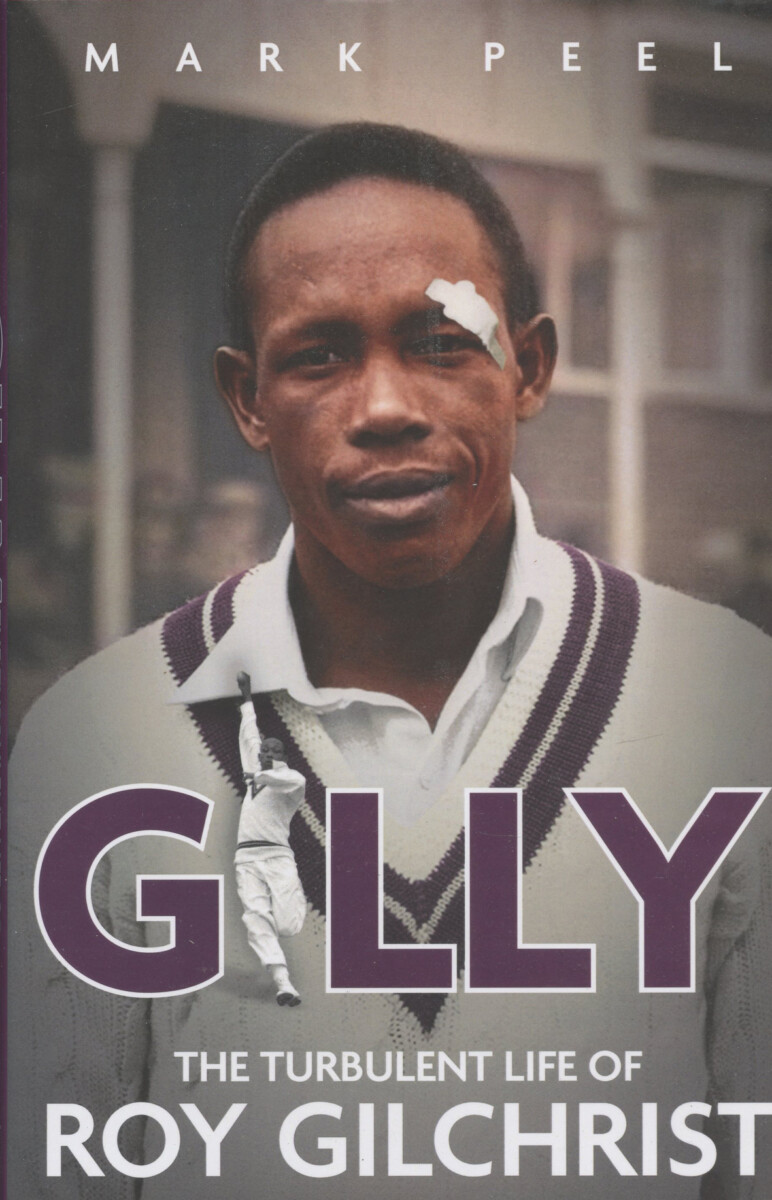

Description

224 page hardback biography of the ex-West Indian Roy Gilchrist who is among the few Test cricketers to also do time.

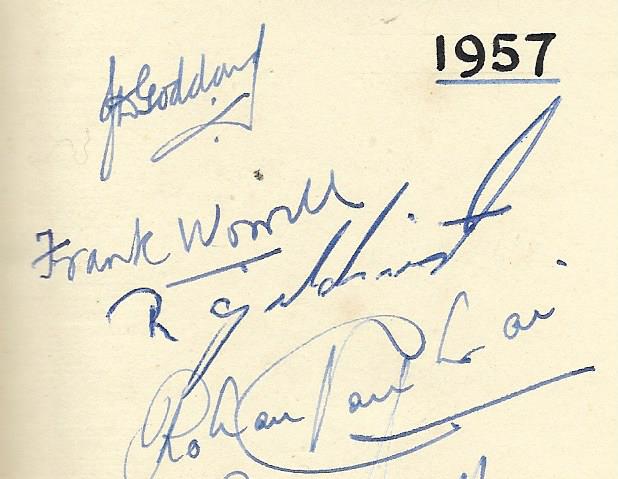

Gilchrist wasn’t allowed to go to school and when selected for the 1957 tour to the UK after just six months of rep cricket, he had to practice signing his signature…

Additional information

| Year Of Publication |

|---|

1 review for Peel, Mark – Gilly, the turbulent life of Roy Gilchrist, last copy

Add a review Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a review.

Related products

-

Harvey, Neil – My World of Cricket (autobiography)

$13.75 Add to cart -

Knight, James – Lee to the Power of 2

$16.50 Add to cart -

Frith, David – My Dear Victorious Stod (limited edition)

$104.50 Add to cart -

Sale!

Byrell, John – Thommo Declares! Cricket’s most colourful larrikin

$22.00Original price was: $22.00.$5.50Current price is: $5.50. Add to cart

Ken –

Had racial issues not delayed Frank Worrell’s assent to the West Indian cricket captaincy, Roy Gilchrist may have become one of the most celebrated Calypso cricketers of all.

Denied the opportunity to tour Australia with the 1960-61 all-stars, the world’s fastest and most volatile bowler was run out of the game before he’d even reached his peak.

The game’s ultimate bad boy, Gilchrist was divisive, dangerous and paranoid. His captain, fellow Jamaican Gerry Alexander, labelled him ‘illiterate’ with ‘maniacal tendencies’.

An enraged Gilchrist ran at Alexander with a fork one night. He branded his own wife with a hot iron and did time – he was a nasty, violent man.

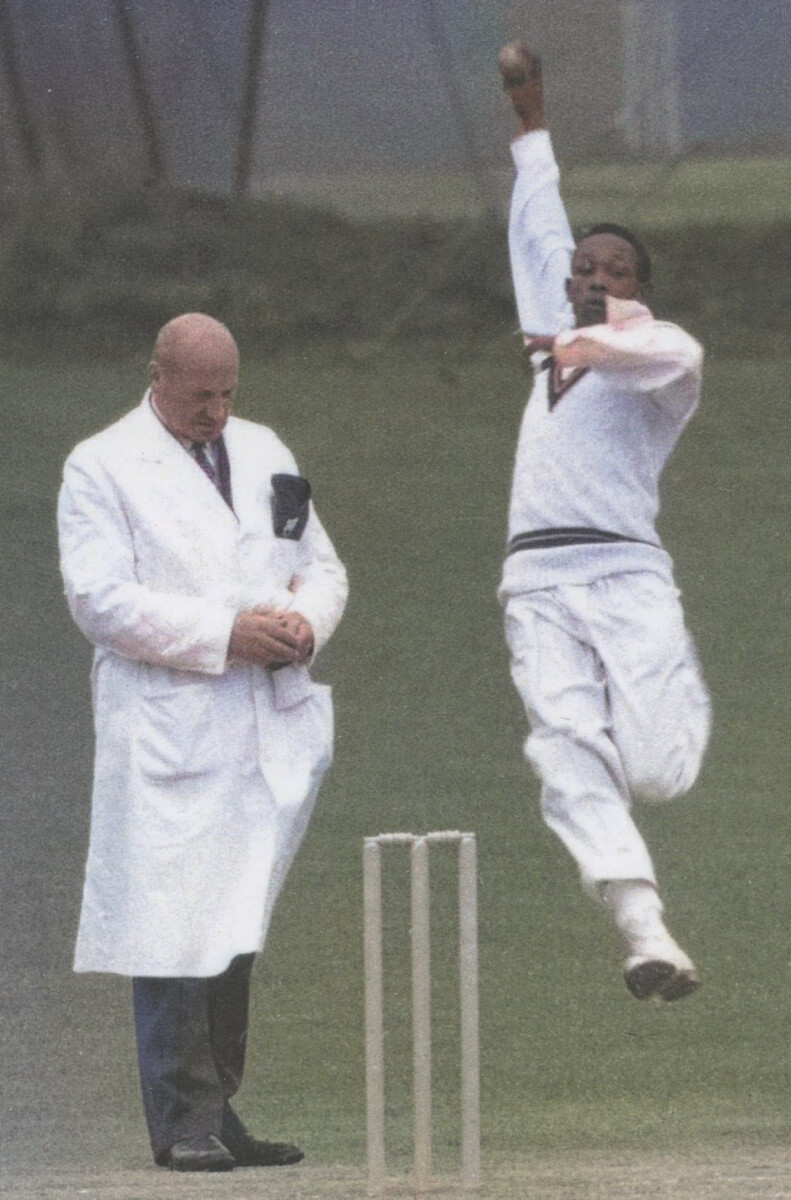

Despite his diminutive statue – he was just 170cm (5ft 7in) and barely 63kg (10 stone) – he bowled at a tremendous speed upwards of 145km/h (90mph) from a 26-yard run which sometimes he extended if he wanted to hurt someone. He’d bounce the tailenders and show little contrition if he happened to hit them.

For Gilly the madman, cricket was a war. ‘They have a bat; I have a ball. May the best man win,’ he’d say.

Fast-tracked after just 12 months of plantation cricket into a tour of England, he was genuinely scary and if a batsman happened to hit him for four, a deliberate beamer would inevitably follow.

He behaved only for those he respected, like his first touring captain John Goddard and for Worrell, the much-loved master diplomat initially denied the captaincy because he was black.

He abhorred Alexander who he said looked down his nose at him and reckoned he was a chucker.

The youngest of 22 children, Gilchrist wasn’t allowed to go to school and had to practice signing his own autograph leading into the ‘57 tour.

Alexander reckoned Gilchrist totally unmanageable and sent him home for bowling deliberate beamers at one of Alexander’s friends in a non-consequential end-of-tour game in India.

Worrell and others fought for him, begging that he be reinstated. Had Worrell not chosen studies over cricket and been unavailable for the tour, he and not Alexander would have captained the team.

With 71 wickets in 12 first-class matches on tour, Gilchrist was at the peak of his powers, the fastest bowler in the world.

In Bridgetown in 1958, his first ball of the Test soared over the batsman’s head and struck the wall at the foot of the George Challenor Grandstand on the full.

After the much-celebrated tied Test in Brisbane in 1960, Keith Miller called for Gilchrist to reinforce the Calypsos. Worrell would have loved that, but having only just assumed control, he didn’t have the Caribbean-wide influence he was soon to command.

Gilly, the turbulent life of Roy Gilchrist is a rollicking, astonishing read with its own rough edges. Author Mark Peel says so lethal was Gilchrist that had he been allowed to tour in 1960-61, the West Indies would most certainly have won, rather than being beaten 2-1.

A shunned Gilchrist took his talents to English league cricket where he had 12 clubs over a stormy 28-year period noted for his run-ins with authority, opponents and crowds who regularly baited him, calling him a black bastard and worse.

When offered the opportunity to return to Jamaica for a fresh start, Gilchrist bowled badly, misbehaved, sounded off against his superiors and was again barred, this time for good.

With 57 wickets in 13 Tests, including 40 in 10 under his nemesis Alexander, Gilchrist’s strike-rate was a formidable 56 balls a wicket.

A huge kangaroo leap at delivery, the fastest of arm actions and the stamina to bowl for hours on end were his signatures.

He would have opposed the 1955 Australians only for rain to wash out an island match.

Many who were to face him, like Bobby Simpson and a teenage Ian Chappell said he was lightning quick, as fast as anyone they ever opposed.

Chappell was next man in when Gilchrist, representing Darwen in a friendly against a Commonwealth XI, lost his temper and punched Lou Laza, an Australian playing professionally in the Bradford League.

Brandishing his bat like Javed Miandad, an enraged Laza struck Gilchrist on the forehead, before being struck himself after Gilchrist uprooted a stump.

The incident was typical of Gilchrist the firebrand. He was the roughest of diamonds, impetuous, unruly and unbalanced – totally disdainful of authority or cricket’s good name.

He missed a Test match in India having contracted VD after a night with a Bombay prostitute, and weeks later, in Delhi, almost another after another fling.

It was amazing he didn’t kill someone with his beamer, which he’d often deliberately throw.

Peel’s biography lacks statistics – a common theme with his otherwise-excellent offerings – and there are very few photographs of Gilchrist. Those that are included are reproduced on poor paper stock, cheapening an otherwise riveting read. – KP