News

REVIEW: MY SONG SHALL BE CRICKET

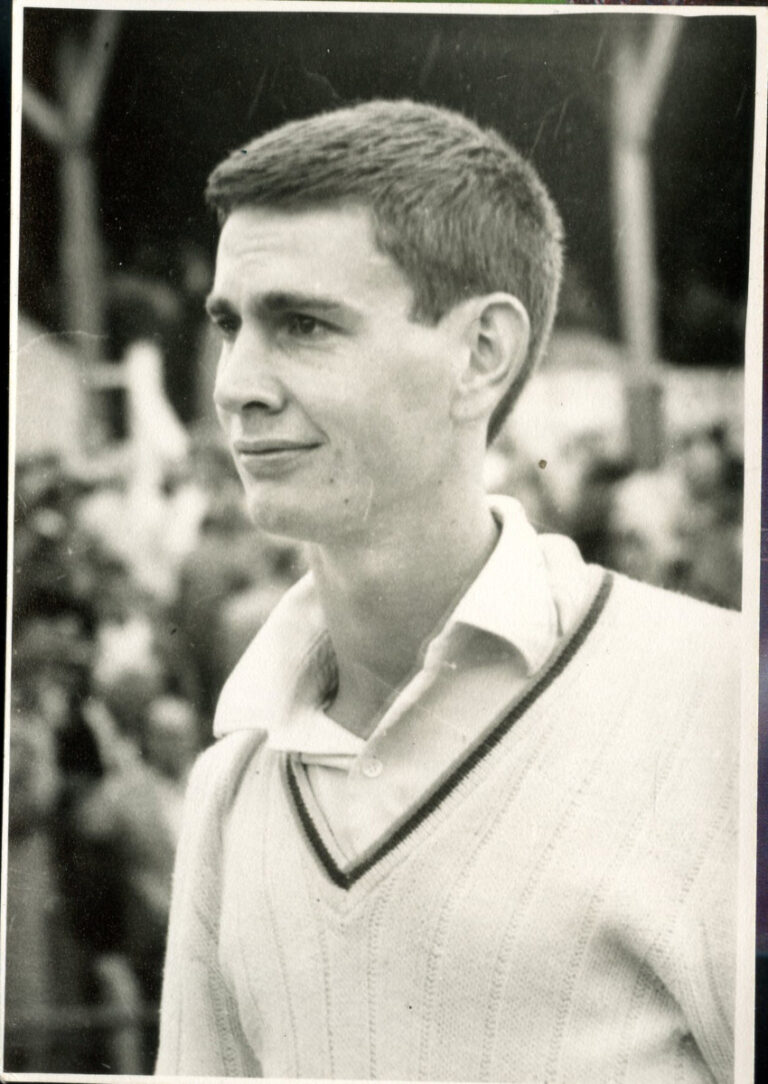

Franklyn Stephenson was an extraordinary, innovative cricketer. First time at the MCG he took 10-46. His slower ball became the most famed in English cricket. He was switch-hitting long before KP. He was the last to do the double of 1000 runs and 100 wickets.

Yet his career is forever underrated – and tainted.

At 23, he accepted $US100,000 to join the West Indian rebels in South Africa and was immediately shunned by selectors and sets of administration all over the Caribbean.

At 23, he accepted $US100,000 to join the West Indian rebels in South Africa and was immediately shunned by selectors and sets of administration all over the Caribbean.

‘They imposed a life ban on us,’ he said. ‘They’ll look back and say that the majority of the players that went to South Africa were past their best and had been dropped from the West Indians team, but there was one player, the youngest player in that team, who hadn’t played a game yet.

‘For 15 years I was able to dominate wherever I played and whoever I came up against. Records and statistics show that, for the period in which I played, I always came out on top.’

A journeyman, incredibly popular everywhere he played, almost all of Stephenson’s cricket was at English league, county or South African provincial level. Just eight of his 219 major games were with Barbados.

On his Caribbean first-class debut at St Kitts he made 165, having gone in as a nightwatchman against a Leeward Islands attack headed by Andy Roberts.

His only seasons of truly international cricket were with the rebels in 1982 and again in 1983 when his all-round feats against the likes of Barry Richards, Graeme Pollock and co. made him, along with the fiery Sylvester Clarke, the most powerful player in the West Indian combine.

In his foreword, Sir Garfield Sobers calls Stephenson ‘one of the most competitive players to have graced the game’.

A two-time winner of the UK Allrounder of the Year Award, Stephenson once took 10 wickets and scored two centuries in the same match – and finished on the losing side.

He’d been a reluctant ‘rebel’ but says history has proved him and the other West Indians involved in the two tours right.

In his autobiography My Song Shall be Cricket, he says: ‘I will always feel myself lucky to have been part of the intervention that became a catalytic force for positive change in South Africa.’

Barbados officials treated him ‘viciously’, he says and he had no choice but to become a journeyman, playing on four continents and for more teams than almost anyone pre the Twenty20 age.

Among his proudest achievements in English cricket was a century and 7-117 for Nottinghamshire against Yorkshire.

His MCG debut, for Tasmania against Victoria in 1981-82 saw him take 4-27 and 6-19 as the Vics tumbled to all out 83 on a wicket which grubbed and soon afterwards was dug up.

He developed a slower ball when they weren’t fashionable. And switch-hit an amazed John Emburey in a county match.

Sobers believes ‘Franky’ to be one of the best players never to play Tests.

Stephenson now has his own Cricket Academy, nurturing and encouraging the next streams of young Bajan hopefuls with stars in their eyes, ‘just like me when I was their age’.

Had administrators in the Caribbean in the mid-80s had more foresight, the revered depth and reign of West Indian cricket could have remained a constant. He says the lack of support from local administrators back then was blatant… and costly

‘The noted absence of select ex-Test players (back then) seemed to be standard,’ he said.

He regarded his time in South Africa as ‘simply amazing’ even if he hated having ‘honorary white’ status. He was saddened to be so scorned back home.

Within a decade he hopes for the first graduate from his Academy to emerge as a West Indian Test player. — KEN PIESSE