News

Reviewing Karl Schneider

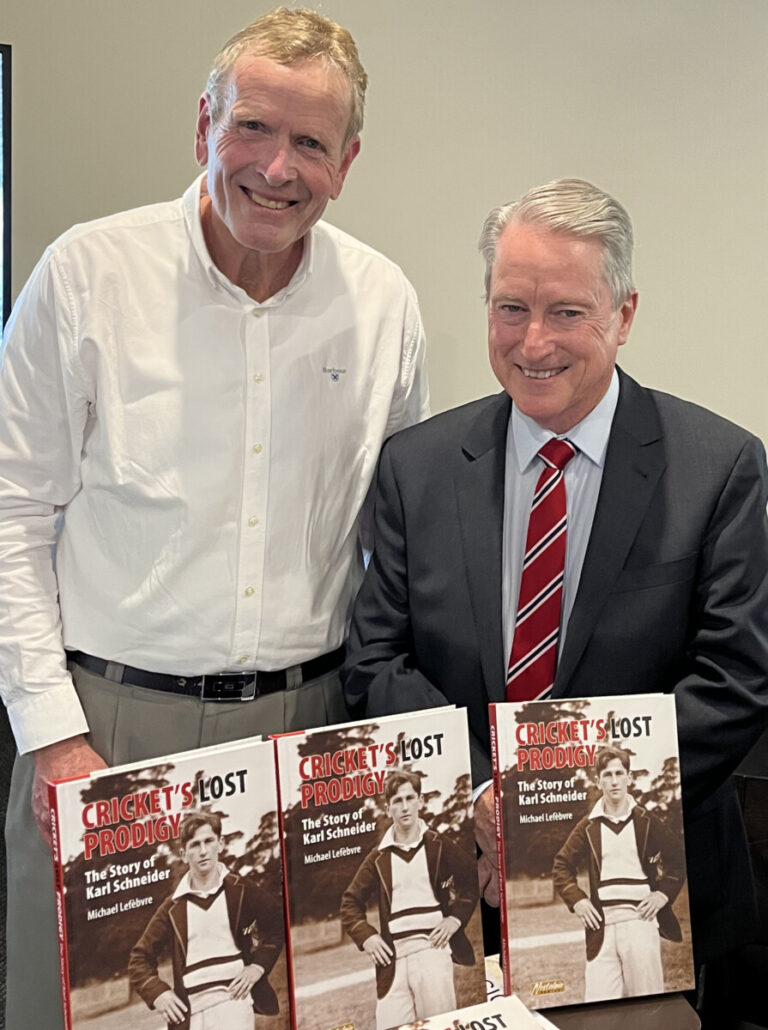

This review from Charles Barr in the Association of Cricket Historians quarterly journal, soon to be released:

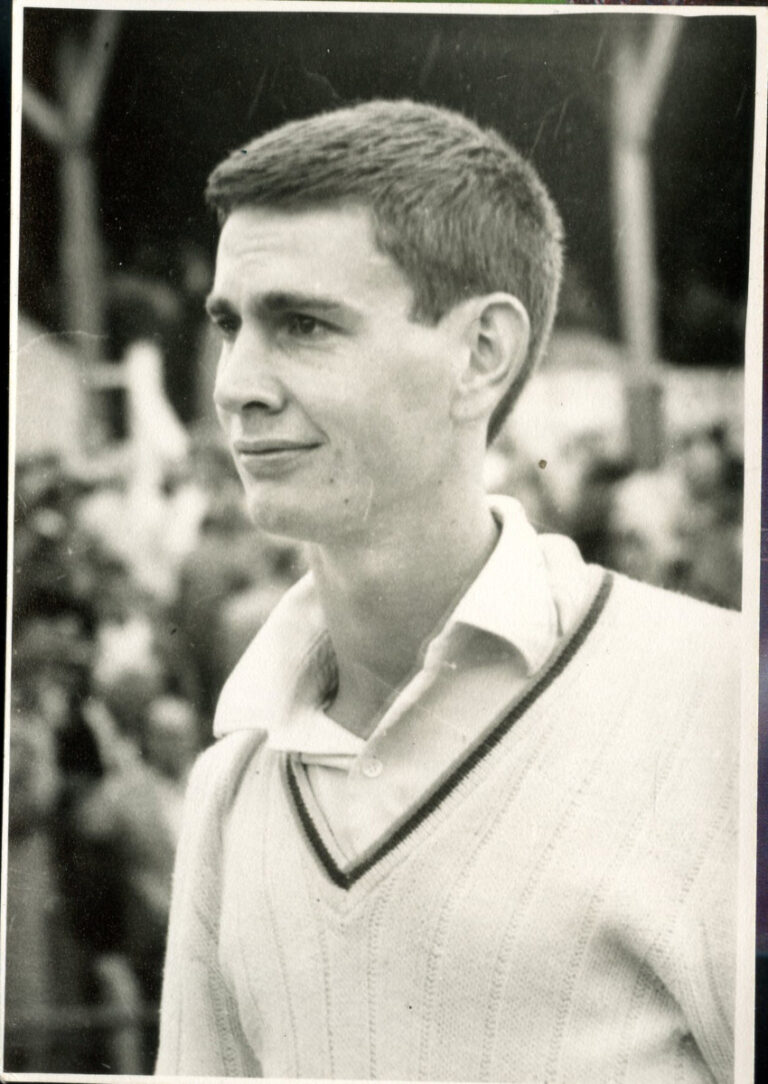

Archie Jackson, Karl Schneider, Don Bradman, three major young Australian batting talents of 1927. Michael Lefèbvre’s book makes a convincing case for ranking them together, as of that moment. Schneider and Jackson toured New Zealand with an Australian A team in early 1928, Bradman staying behind as a reserve. For all three, the tour by England in 1928-29, first home Test series in four years, loomed up as a great chance of breaking through.

Archie Jackson, Karl Schneider, Don Bradman, three major young Australian batting talents of 1927. Michael Lefèbvre’s book makes a convincing case for ranking them together, as of that moment. Schneider and Jackson toured New Zealand with an Australian A team in early 1928, Bradman staying behind as a reserve. For all three, the tour by England in 1928-29, first home Test series in four years, loomed up as a great chance of breaking through.

Both Jackson and Bradman would seize that chance, but by the time the series began in November 1928 Schneider was dead from leukaemia, aged barely 23, after collapsing towards the end of the NZ tour. In 20 first-class games, mainly as an opener for South Australia, he averaged close to 50.

I wonder how many readers will have recognised the name: I failed to, as did two cricketing friends from Down Under, both knowledgeable about the game and its history. Jackson of course died just as sadly, just as young, but he had by then, at 23, made an Ashes century, and had toured England. Widely acclaimed as ‘a new Trumper’, he later inspired a fine biography by David Frith, The Keats of Cricket (1974, new edition 1987). Schneider had been promoted as a ‘new Bardsley’, potential successor to the left-handed opener Warren Bardsley, recently retired – a substantial but less romantic figure than Trumper. Nor is it easy to link Schneider with a poet. From evidence skilfully deployed by Lefèbvre, it seems he could well have gone on to form a link in the solid left-handed opener chain from Bardsley to Morris to Lawry to Khawaja. If only.

The name of Karl Schneider disappeared from the Births and Deaths section of Wisden in 1956, victim (unlike Jackson) of the cull of most of those who died before 1936. A forgotten figure indeed, unlike Jackson, unlike Bradman.

The book must have a better chance of selling in Australia than in England, since Schneider never lived or played here, nor played against any English side. The one English link is with Patsy Hendren, who worked with him briefly when acting as coach to South Australia in 1926-27, rating him highly. Lefèbvre is wrong to claim that Hendren played professional football through most of the 1920s for Brentwood (never a Football League club) rather than Brentford: an easy error, since this is so much an Australia-centred book, and as such very informative about the years of Schneider’s brief life.

His roots were, predictably, German: his father Vincent moved from Germany to work in London for a decade, never got to like the people, and emigrated to Australia in 1887, without losing his ‘thick German accent’. Name and accent naturally caused problems during the war – it was a surprise to learn that name changes, so common in England, were prohibited – but the family came through it, and Karl was able to embark on a brilliant career at the Catholic St Xavier’s school in Melbourne: brilliant at football as well as cricket; then moving to Adelaide, and giving up the football, in order to give the best possible chance to his future in cricket.

And it was all going so well. The pathos of the personal story cannot fail to hold the attention of any reader, even if the name has long been forgotten by Wisden.